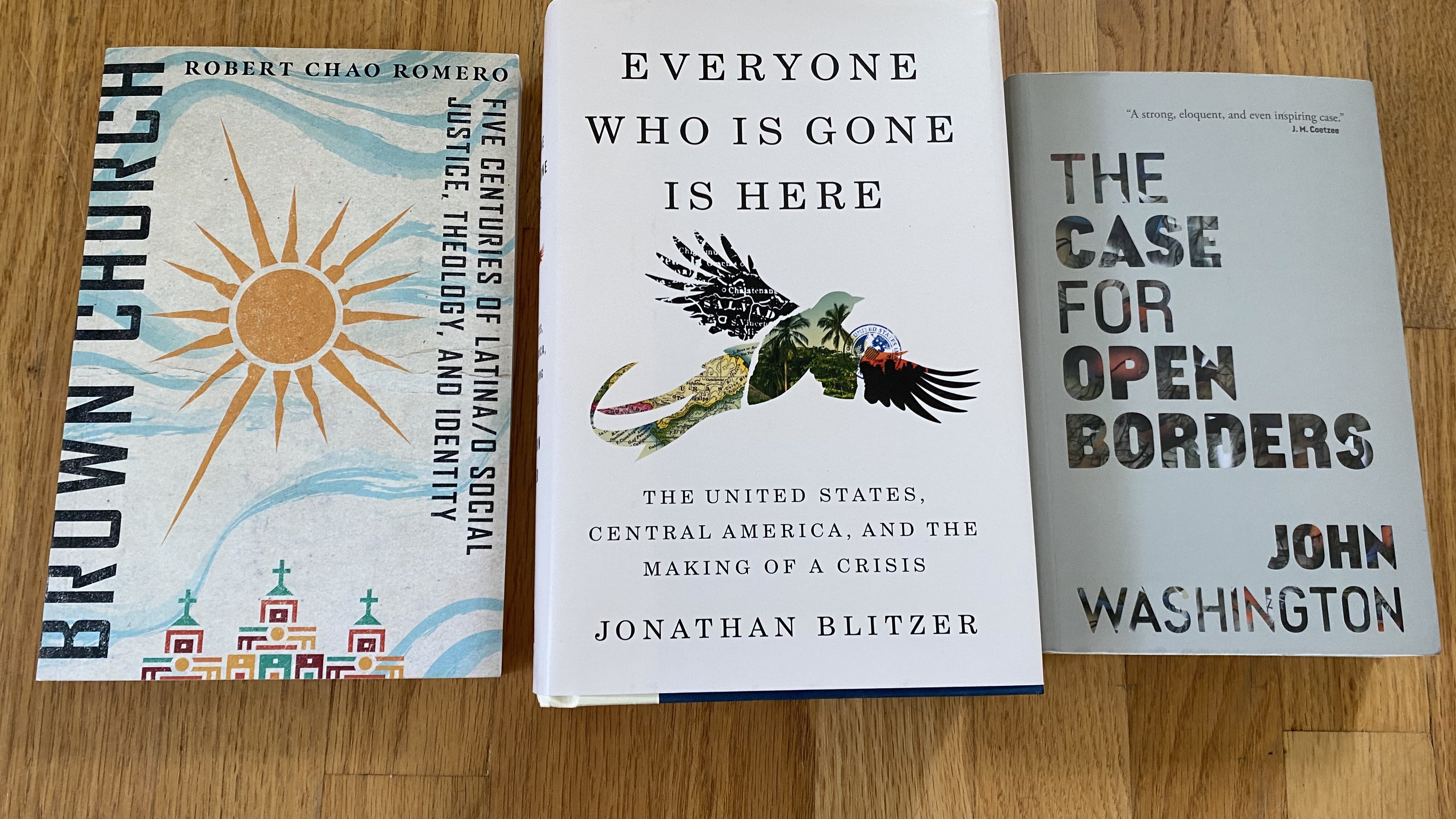

The following provides a summary of three books that I’ve found helpful on the topic of immigration. They aid in providing a clearer understanding of the historical context surrounding the issue. Each of the books approaches the subject from a different perspective; and yet, each of them has much in common with the others. In fact, the first does not treat immigration as its primary topic, but the subject is never far from the surface, and its broader topic of the “brown church” continuously explores issues surrounding immigration. The second dives directly into how US policy has affected the lives of real people caught in the swirl of chaos surrounding international migration. The third presents a very tightly woven argument for changing US policy on immigration and border management to allow for much greater freedom of movement.

Brown Church: Five Centuries of Latina/o Social Justice, Theology, and Identity – by Robert Chao Romero.

In this book, Romero invites his readers to look at the five-hundred-year history of the Latina/o church in the Americas and the theology that informs its life. He explores the beginnings of the Chicana/o movement in the United States and the recognition of the challenges their community has faced due to events in history. He begins by examining the confiscation of much of the western US from Mexico through the treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo and the blatant racism which greeted many of the peoples of those territories after being folded into the U.S.A. Romero shows how many in the Latina/o community today faced with similar issues respond in like fashion as did those who faced Roman occupation in Jesus’ day (the Sadducees, Essenes, and Pharisees/Zealots).

From there, Romero backs up and dives into the over 500-year history of resistance to the coopting of Christianity by colonial powers to oppress indigenous peoples. He begins by examining what seems to be a banal assertion of someone in a Latin American country. Romero shows that when someone says, “I’m Spanish,” this assertion is rooted in a privileged, racist perspective that has taken root in Latin American society. He shows that the resistance to this perspective began in a prophetic sermon delivered before Christmas on the island of what is now the Dominican Republic in 1511, by a Dominican Friar (Antonio de Montesinos) asserting that the war on indigenous peoples was immoral. This rebellion against the prevailing perspective of the conquerors continued with the work of Bartolome De La Casas. He challenged the position of the church authorities and warned that the witness of Christianity will be irreparably damaged. He stated that the “heralds are not pastors, but plunderers, not fathers, but tyrants,…” (page 69). Next, Romero explores the very mixed cultural heritage embedded in current Latin American and Chicana/o contexts. He illustrates this mixture by describing his personal ethnic and racial heritage, and how his family perceived that heritage by privileging European (Spanish) aspects of that heritage. He identifies this perspective as idolatrous (page 79) and a current area of struggle for those in the “Brown Church;” and yet, that perspective has been challenged throughout the past two centuries by a range of prophetic voices that he briefly describes.

Romero then asserts that the pivotal point in the history of the othering of “brown” peoples came about in 1848 with the conclusion of the U.S.-Mexico war. He describes in detail the provisions of the treaty ending the war which relegated former peoples of Mexico to gaining citizenship “at the proper time” at an undetermined future (page 106). He details the sordid history of how citizenship was only passed to those who appeared as “white” and not of mixed or darker skinned peoples (pages 106 – 109). In addition, Romero describes the seizure of lands by the newcomers to this territory through various means that stripped the former citizens of Mexico of ownership in these new areas of the United States. The theology of Manifest Destiny gave support to this seizure as well as the “racial segregation and socioeconomic and political marginalization” that followed in the wake of the transfer of these territories from Mexico to the U.S. (page 119).

Romero then describes the rise of Liberation Theology. He begins by telling how the religious background of Cesar Chavez laid much of the foundation for his practices in the farmworker movement. Romero then highlights the importance of those in the Latin American church recognizing that God holds a strong preference for helping the poor, and this preference cannot be ignored. Though many in positions of influence within the Latin church were slow to embrace this perspective, Archbishop Oscar Romero being one of them; he and others eventually came around to see the necessity of strongly heralding a blending of social responsibility into the message of the church.

Romero finishes his book with an examination of the social identity of Brown Christians. He states that “we claim a social identity that encompasses our love for Jesus, our rich and diverse God-given cultural heritage(s), and our passion for justice and liberation. We no longer leave any of it outside the colonizer’s door” (page 214).

Everyone Who is Gone is Here: The United State, Central America, and the Making of a Crisis – by Jonathan Blitzer

In this book, Jonathan Blitzer contends that for “more than a century the US has devised one policy after another to keep people out of the county…” and for “more than a century it has failed” (page 2). This book seeks to provide readers with a glimpse of the effects of those policies on real people. In particular, he draws our attention to the recent situation the US finds herself in due to the shifts in migration patterns beginning around 2014 when larger numbers of migrants started coming from the Northern Triangle of Central America (El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras). Yet, he does not just restrict himself to current events; but sets the context for those events by beginning his story in the 1970s.

Blitzer divides the book into four main sections. Each of the first three sections center on the life of one individual that serves to highlight the complexity of various aspects of the problems endemic to our immigration system. The first section details the events in the life of Juan Romagoza, one of the foremost figures in the Sanctuary Movement during the late 1980s. Blitzer traces the events in his life beginning with his childhood and early medical training during the war years in El Salvador. The gripping events in his life during this period of intense unrest form the backdrop for describing the macro-effects of political decisions in both the US and Central America to the lives of people on the ground.

The second section presents events surrounding the life of Eddie Anzora and others. Through the events surrounding Eddie’s life, the reader sees details about the rise of Central American gangs (particularly MS 13), and the spread of these gangs in the LA area and other parts of the US. The stories of Juan and others continue in this section as well.

The third section highlights events in the life of Keldy Brebe de Zuniga beginning with her experience of the devastating hurricane that drove her at the age of 14 from her home in Honduras to eventually emigrate to the US. Blitzer presents the absolutely harrowing experiences Keldy faced. These events serve the book’s purpose by illustrating the effects on vulnerable people of the revolving door through which both innocent people and criminal gangs move between the US and Central America, much of it the outgrowth of the political unrest in each of the countries that have had differing engagement with the US.

The fourth section ties much of the story together with each of the three main characters as well as other minor characters presented in their current situations in either the US or Central America. The connections between them and their individual circumstances weave together in surprising ways that show the tragedy of US and Central American relations over more than fifty years.

The Case for Open Borders – by John Washington

In this tightly woven argument in favor of radically changing the prevailing perspective on international borders, the author, John Washington, begins by illustrating the human costs that the current border situations around the world levy upon vulnerable peoples. From there, he goes on in rapid fire fashion to present his arguments for change from multiple perspectives.

In chapters 2 and 3, Washington asserts the importance of recognizing the unfair nature of the current system. By tracing the current perspective on international borders back to the treaty of Westphalia, and then to the current international system set in place at the end of World War II, he shows that though this system has brought relative stability, the costs have been and continue to be enormous. We must recognize that this status quo has only been achieved through ruthless, violent conquest. In that context, the notion of citizenship “has always been a mercurial one” (page 51). In addition, he notes the absurdity of the fact that “44 percent of the international borders of Africa are straight lines…[and] Worldwide, 40 percent of national borders were drawn by two countries: Britain and France.” (page 61).

Next, Washington directs his focus to the benefits of immigration for both native and immigrant communities. He confronts the common misperception that immigration hurts native job markets by depressing wages and causing disruption to job markets. He directs his readers to recognize that “neither national economies nor job markets are zero sum.” (page 69). He states that “an influx of immigration does not lead to lower wages or higher unemployment” (page 70). He presents his readers with two examples to illustrate the effects of immigration on job markets (one negative and one positive). In 1929, shortly after the stock market crash, the US launched the Mexican Repatriation Act to send US residents of Mexican descent across the border in the hopes that more jobs would be available to those left in the border communities. This in fact proved to be a detriment to the job markets. Instead, a reduction in immigrant workers in these communities reduced the demand for other jobs, “especially skilled craftsmen, managerial, administrative, and sales jobs mainly held by natives” (page 74).

The second example was the Mariel boatlift from Cuba in 1980. During this influx of new migrants into the Miami area, studies have shown that the economy, far from seeing significant job market disruption, experienced both calm and stable growth. Unfortunately, as Washington states “Blindness or ignorance to history is one of the primary impediments to ‘solving’ the immigrant crises” page 92).

Of additional significance, a 2017 government study during the first Trump administration found that from “2005 to 2014…the US asylee and refugee population paid $63 Billion more in taxes than they received in benefits. And the per capita net effect of each refugee or asylee was positive by $2,205 compared to the national average of $1,848…” for the native-born population (page 79). In addition, estimates show that efficiency gains from “eliminating barriers to trade, capital flow, and human mobility…would increase GDP” significantly, as much as 4.1 percent (page 82).

Next, Washington makes the point that borders throughout the world seem to create far more problems than they solve. For the most part, borders have been arbitrarily constructed and disrupt the peaceful existence of peoples in given regions where “movement that had been happening for thousands of years is now illegal” (page 111). He raises the question, “What is a country?” (page 111) and then proceeds to show how “artificial states cutting community ties by imposing borders, [and] pitting ethic groups against each other as they jockey for national power” (page 114) serves no one well. He also shows that geographical landscapes, have “little to nothing to do with borders” (page 114).

Then, he points out the extreme inequity in how border enforcement treats rich versus poor. Essentially, “poor people almost never get a pass” (page 118). And on top of that, the poor are more in need of moving locations when disaster strikes, be it from natural causes (flood, hurricane, drought), or from political oppression and war (or a combination of all). More absurdly, the policy statement from the US in the recent past has been to say to those wanting to come to the US “stay at home…quedate en casa”…[b]ut you can’t say to someone whose home was destroyed by a hurricane to stay home” (page 139-140).

So, what does Washington envision as an alternative? He begins by stating the obvious – imagining total lockdown is much easier than imagining more open borders, even if lockdown is “impossible to enforce” (page 141). He describes the horrid conditions in our current detention system. He then contends that we should reallocate those resources to processing asylum and immigration requests. We should grant legal status for migrants so that they can participate in our economy. He asserts that “punishment of people who migrate doesn’t work as a deterrent”…and no study “has been able to demonstrate that threat of punishment stops people from crossing or recrossing the border” (page 154). Washington then contends that we should consider welding “the concept of free migration to free trade” (page 157). He shows how this could be implemented by describing the multiple free migration zones between countries in the EU, whereas of 2021, “nearly half a billion people in twenty-six different countries can travel freely within 1.6 billion square miles…” (page 158). He also cites other such zones within both Africa and South America where countries allow free movement and provide relatively easy potential for obtaining residence and work permits (page 159). He states that “even the United States, until 1968 had a more open stance toward regional movement (page 160). At bottom, Washington contends that we need to increase our imagination so that borders “themselves do not need to be changed, only their role in establishing groups by birth and restricting movement on this basis” (page 165).

In addition, misperceptions regarding the economic flows between poor and rich countries coupled with incorrect views of the number of immigrants who are part of the total US population continue to contribute to prejudicial anxieties. He cites a 2016 study that shows “when you tally up all the financial resource exchanges between rich and poor countries there is an annual net outflow from poor to rich countries that has reached over $1 trillion per year” (page 166). That fact, coupled with the errant view that most people in the US estimate that 40 percent of the US population is comprised of immigrants when in reality it is 14 percent (which is within a consistent range for the past 150 years), contributes to people’s anxiety. Instead and unfortunately, many people believe that immigrants have overrun our country and want to suck our economy dry, and that we should be worrying about our own problems.

Washington finishes his work with a very tight summary of his arguments – “Twenty-one Arguments for Open Borders” (page 180). These include:

- “Borders have not always been” – we need a new imagination similar to what helped eliminate slavery. We need to remember that there were no “substantial fences or walls along the US Mexico border until the late 1990s” (page 184).

- “Immigrants Don’t Steal Jobs – They Create Them.” – “Economic studies across the political spectrum tell us that immigrants create more jobs than they take…,” and the jobs they have within the US are concentrated in critical supply chains and agricultural jobs that support the creation of other jobs (pages 186-187).

- “Immigrants Don’t Drain Government Coffers.” They pay large sums in taxes, and yet, are not eligible for many of the social and government services available to the rest of the population. In addition, they use those services for which they qualify far less than the native-born population (page 187-188).

- “Borders Don’t Stope Crime and Violence They Engender Crime and Violence.” By eliminating or revising current border restrictions, the elicit gains criminal smugglers acquire from trafficking people would be immediately undercut. In addition, federal prison sentences associated with immigration violations would be significantly reduced (in 2011 over 30% of federal incarcerations were for immigration offences) – (page 189).

- “Immigrants Don’t Threaten Communities They Revitalize Them.” – “When immigrants arrive to a community, crime rates drop, property values jump, and neighborhoods get a shot of cultural energy and economic vitality” (page 191).

- “Migrants Rejuvenate.” Many cities in the US have seen declines that could be reversed by infusions of immigrants (see the example of Springfield, Ohio – not mentioned in the book).

- “Open Borders Doesn’t Mean a Rush to Migrate.” – “Most people want to stay home,” and studies have shown that even those who indicate a desire to migrate rarely actually undertake a move (pages 194 – 195).

- “The Nonsense of Nationalism.” Washington contends that “humans don’t group into tidy and geographically distinguishable communities. Rather, we all bear multiple identities and cycle through overlapping communities” (page 197).

- “Closed Borders are Unethical.” Washington reminds us that our position within the borders of a particular country is always unearned, and restricting access to others who are in need based upon arbitrary or accidental issues associated with birth is unfair and unethical.

- “Brain Drain Ain’t a Thing.” – “Brain drain is a false assumption that there is a fixed and limited amount of skilled labor and therefore the professionals from poorer countries should not be allowed to migrate” (page 201).

- “The Libertarian Case.” Restricting the free movement of people goes against the notion of individual freedom to make basic decisions affecting an individual’s life. Washington does not completely ascribe to the individualistic perspectives of most Libertarians, but he does recognize and support their arguments for individual freedom as long as human connections are still recognized and fostered.

- “Dehumanizing Border Machinery Targets Native Residents Too.” Washington cites the intrusive nature of border enforcement programs, and the social costs associated with the police-state-nature of their enforcement programs.

- “Opening Borders is Economically Smart.” Economists have estimated that economic gains from eliminating current border restrictions would result in “estimated gains [in global GDP] from 50 to 150 percent” (page 206).

- “Open Borders are an Urgent Response to the Climate Crisis.” Large numbers of people are estimated to be in danger of needing to move in the coming decades. Extreme border restrictions make this untenable and cruel in the extreme.

- “Open Borders as Reparations.” US foreign policy over the past 75 years has caused untold amounts of chaos and distress in the world. Our policies in Latin America alone (see – United Fruit Company) should drive us to open our borders to those in distress in those countries (not to mention the Middle East and Afghanistan).

- “World Religions Agree: Open the Borders.” – “Living to the standard of any of the world’s major religions requires, an openness, and welcomeness, and a hospitality that closed borders do not permit” (page 214).

- “Closed Borders are Racist.” Washington contends that “a web of multi-lateral visa agreements privilege certain passport holders, and allow their free movement, while denying and immobilizing others. Such discrimination, while based on nationality, overlaps with both class and race” (page 214).

- “Walls Don’t Work.” Though they do work to make life miserable for people on one side or the other of a wall, they do not work to keep people in desperate situations out.

- “’Smart’ Walls are Stupid.” Smart walls that avail themselves of the most sophisticated technology in much the same way as standard walls do not keep people out but “slow or divert people” to more dangerous routes (page 220).

- “The Right to Migrate /The Right to Remain.” In the end, Washington recognizes that the appeal for open borders “rings empty without the attending fight to improve conditions in the countries migrants flee” (page 221).

- “The Simple Argument.” – “Barring small island nations, all countries’ borders have been drawn in blood. Genocidal slaughter and ruthless imperialism helped form the United States and bottom-lined the wealth of France, the UK, Spain, Germany, Israel, and other countries in the global North. To claim the right to stop a migrant from crossing a line that was previously and flagrantly trespassed by the controlling elite (or their ancestors) is absurd, and in the most basic sense, unfair” (page 222).

My Reaction:

After reading and re-reading each of these books, I am struck by the complexity of the issues surrounding immigration. The history of our country’s approach to both immigration and all things associated with borders (their establishment, roles, laws, etc.) makes the search for an appropriate and feasible solution to our current predicament, both in the US and throughout the world extremely difficult. Nevertheless, human decency requires that we face this challenge head-on and strive to open our imaginations to search for solutions that reflect kindness and compassion.

Our approach over the past 100-years has been neither. It has been especially abysmal over the past 40 years. Political squabbling and scorekeeping have made progress in this area nearly impossible, regardless of who has had the upper hand on the levers of power.

As someone who recognizes the potential for good inherent in well-functioning markets, I hope that at some point in the near future similar gains to what we’ve seen in opening world markets to the movement of goods and materials will also come to pass through the free movement of people. Both history and economics argue strongly in favor of changing our current system toward making it substantially easier for people (especially the poor) to move, live, and work where they want.